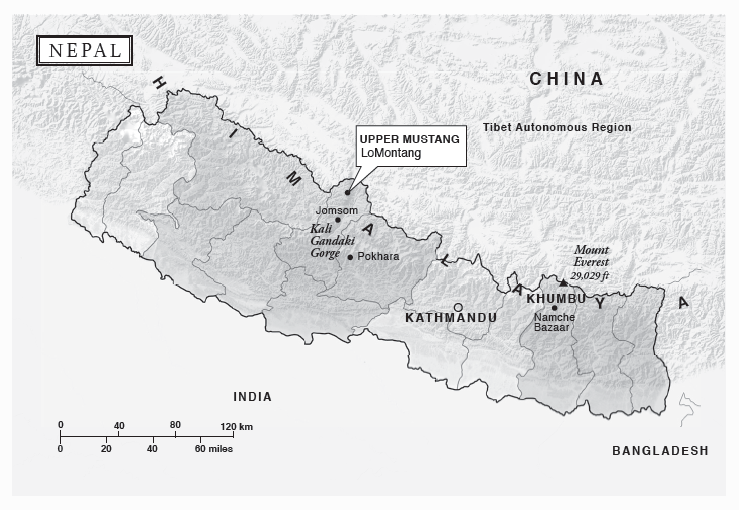

I heard fascinating stories about the Upper Mustang region in north central Nepal while trekking with ethnic Tibetan khampas* and my guide P.K. in the Annapurna range during the late 1960s. Mustang was further north, beyond the Kali Gandaki Gorge. A military checkpoint at the border prevented us from entering its stunning terrain, but my imagination was fired.

This fascination with Mustang led me to an unexpected development lesson for reviving an extremely poor, isolated community: start by reclaiming fading local traditions and beliefs. In Mustang those core traditions and beliefs anchored in Tibetan Buddhism date at least to the 15th century. Their revival over the past quarter century has made possible better health care and education, opening up new possibilities for its youth in the modern world.

It took twenty years — working through business contacts, cajoling government officials and outlining our humanitarian projects in meetings with Nepal’s King Birendra, but by late 1991 the king accepted my proposal. I would be the first Westerner in many years to explore Mustang, joined by a few friends and family members, before the territory was officially opened to tourists.

Mustang is remote, an extension of the high Tibetan plateau that juts into Nepal. An ancient hamlet situated near the north end of the Kali Gandaki River, near the border of Tibet, is even more inaccessible. This earthen-walled village called LoMontang has been the political and spiritual hub of the Forbidden Kingdom of Lo for centuries.

The king of Mustang, Raja Jigme Bista, was a reticent, self-effacing man, about sixty years old when we first met in LoMontang. He was the Forbidden Kingdom’s sovereign, reigning under the wider authority of the Nepali king for more than a quarter century, the twenty-sixth in an unbroken line of rulers dating to the 15th century.

As with anyone you meet, you’ve got to judge people as you see them. I sensed quickly that Raja Jigme Bista was authentic, believable. He portrayed himself as another in a long line of monarchs despairing for resources to halt the community’s decline as young people trailed away in search of better lives. The government of Nepal had ignored his requests.

I wanted to help. Our foundation had been building and supporting schools, hospitals, and sacred sites in the Himalaya for nearly a decade, and a health center in Upper Mustang. Was there something we might provide for him and his people in LoMontang?

His answer was not what I expected: “We’ve got to restore the monastic school. If we are going to bring this area back to life, it has to start with the temples, the monasteries, and the monastic school.”

Many humanitarian organizations are reluctant to take on projects associated with religious practices. But we soon realized we had stumbled onto a rare opportunity.

The raja explained that historic, spiritually significant Tibetan Buddhist artwork might be shrouded on temple and monastery walls behind layers of smoke from burning butter lamps accumulated over five centuries. He recalled stories from ancestors about fabulous paintings on earthen walls, dating to when wealthy merchants built the edifices.

He wasn’t sure. And we had no experience in ancient art restorations. We didn’t know what we’d find if we mounted a conservation project that could last for years. But he was willing to take a calculated risk on us—and we, on him.

In my next posts, we’ll see how perceptive Raja Jigme Bista was. He understood that a shared cultural identity gives a community ways to unite around a higher purpose, a set of values for investing in a better future. And his hunch about ancient art treasures hidden inside the darkened, slowly crumbling temples nearby proved phenomenally accurate.

For now, below is a spectacular view of the topography surrounding the ancient village of LoMontang. The village structures are barely visible in the deep valley, in the lower center of the image beyond the rocky foreground high above. This photograph is by the gifted restoration expert who has led our LoMontang art restorations for twenty years, Luigi Fieni.

* Upper Mustang was the site of a clandestine military base from which Tibetan khampas, trained and supported by the US Central Intelligence Agency, staged attacks on the Chinese army inside Tibet during the 1960s and 70s. The CIA cut ties with the khampas rebels shortly before President Nixon’s surprise 1972 meeting with Mao Zedong in Beijing.

Map and photo courtesy of the American Himalayan Foundation.

Leave a Reply