Jivan was born with clubfoot so severe that one foot and connecting shin bone resembled a paper clip. Even worse, a series of plaster casts ineptly administered in a rural Nepal hospital not only failed to correct the birth defect, those operations crippled him further with severe tendon damage – all before his first birthday.

Many disabilities treated and corrected at the modern orthopedic institute we touched on last week, the Hospital and Rehabilitation Center for Disabled Children, are congenital. And each year the most common problem among poor children like Jivan admitted to HRDC just outside Nepal’s capital city, Kathmandu, is clubfoot.

If you are born with clubfoot in the United States, the condition often is identified in utero from ultrasound images, or quickly after birth. It typically is corrected by the age of five through a series of manipulations, special shoes, and plaster-of-paris castings. Clubfoot is rarely a lifelong curse.

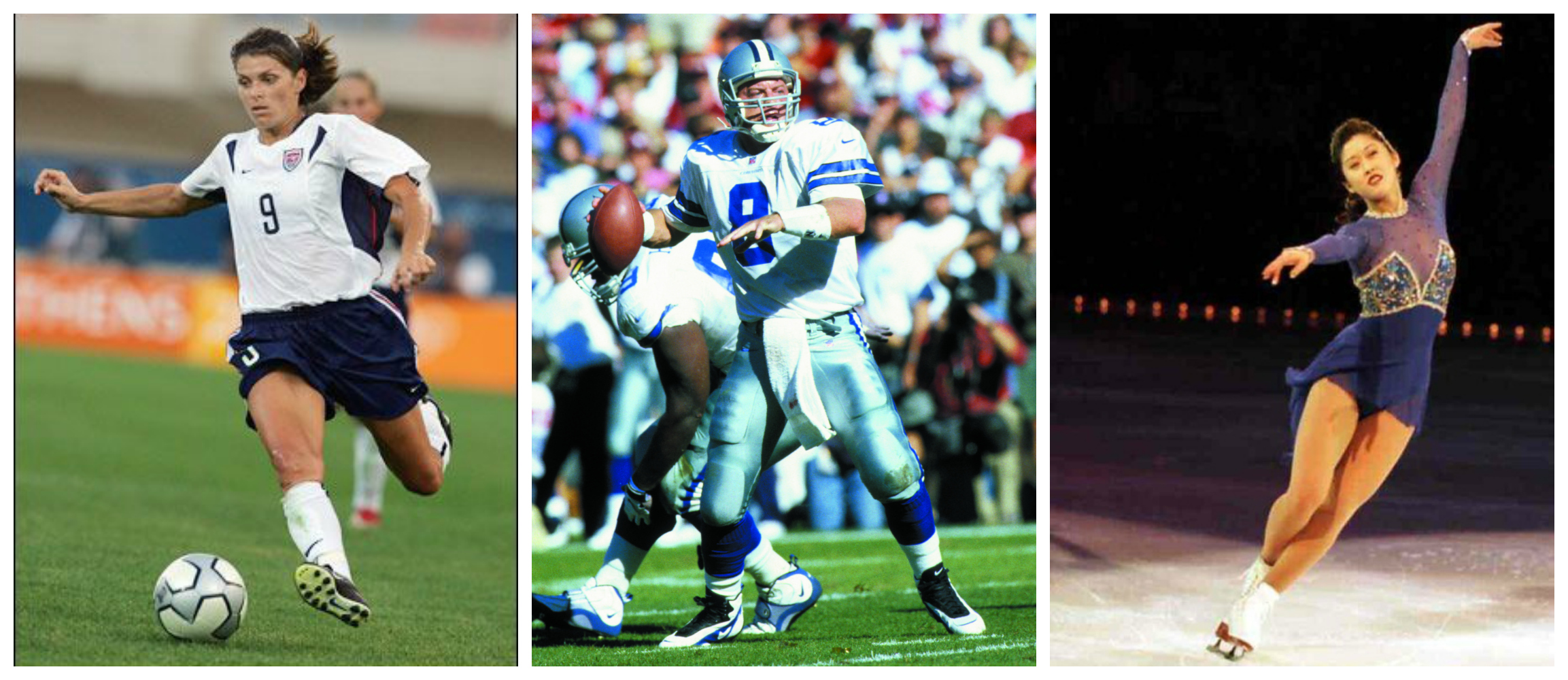

Mia Hamm, two-time Olympic gold medalist on the U.S. women’s national soccer team and ESPN’s greatest female athlete of the past 40 years (Title IX era); Troy Aikman, Fox Sports NFL analyst and quarterback of three Dallas Cowboys Super Bowl champions in the 1990s; and Kristi Yamaguchi, an Olympic figure-skating champion, all were born with clubfoot.

In fact, a baby with clubfoot is born somewhere in the world every three minutes. Millions suffer horrible lives – unable to attend school or work, shunned as beggars or worse in many cultures. Ignorance and superstition are rampant in remote areas where health professionals never visit.

In the mountains of Nepal, most nurses lack much understanding about clubfoot and how it can easily be corrected. The deformity often is never diagnosed, so little kids begin walking around with no crutches or corrective shoes that are part of standard treatment in modern societies.

“The feet turn inward and downward,” explains Eileen Mariano, a former intern at HRDC and now a team leader in a nonprofit family services center in the Bay Area. (Eileen is the oldest of my seven grandchildren.) “Over time the kids are walking on their ankles. This just kills the foot. Huge callous stubs develop on the outside of the ankle.”

Jivan was very lucky. A member of HRDC’s medical team discovered him as the center’s fledgling community services network was making its first journeys to Nepal’s remote areas deep in the mountains. Still short of his first birthday, he was taken along with his mother to the hospital outside Kathmandu for his corrective surgery, the first of five operations he would need over several years. Ongoing physical therapy, which applied gentle massage and manipulation, and four years of special orthotic footwear rounded out his full rehabilitation and recovery.

Founder of HRDC, Dr. Ashok Banskota, adjusts a device for lengthening leg bones of a young patient. Tension created by frequently adjusting pins on the device, known as an llizarov external fixator, can increase bone length by 1 millimeter per day.

Photo courtesy of the American Himalayan Foundation.

HRDC’s embrace of a non-surgical technique for treating clubfoot known as the Ponseti method* brought more sophistication and simpler treatments to regional evaluation centers HRDC established far from Kathmandu. As a result, many major surgeries at the main hospital are no longer necessary. Overall treatment and recovery costs are falling. Most importantly, the psychological trauma inflicted upon young patients through major surgery is reduced. Long family stays once required to support them are far less common.

Introduced at HRDC in 2004 by a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, Dr. David A. Spiegel, the Ponseti method begins with gentle massage and manipulation of the affected feet. (Infants were its first patients.) A series of plaster casts then is applied as the angle of the foot lowers, straightening over time to “plantigrade,” the medical term for right angle to the shin bone. This phase is followed by leg braces and corrective shoes until the child is four or five years old, although studies suggest the method works for children as old as ten.

Dr. Spiegel is a legendary humanitarian physician, dedicating much of his time to treating children in what he has termed “austere” settings in poor countries. A consultant to the World Health Organization in Mongolia and Somalia, he advised HRDC for nearly twenty years. He still practices as an attending surgeon at the famed Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

And Jivan? When we last were in contact three years ago, he had passed his final exams for 10th grade, the last year of high school in Nepal, with ambitions to study medicine and become an orthopedic surgeon. The searing contrast of his own experience in overcoming clubfoot deformity and that of an uncle whose clubfoot was never treated long ago had sown the seeds for that dream.

“My uncle couldn’t walk properly and ended up having his foot amputated,” says Jivan. “He couldn’t earn a living as a farmer or a laborer.”

“I can walk now and my leg looks normal. But life would have been very different for me if I had not been treated at HRDC.”

* The Ponseti method is named for its creator, Dr. Ignacio Ponseti, a medic during the Spanish Civil War who landed later at the University of Iowa to finish his residency. There, he devised his technique by studying the anatomy and functions of a baby’s foot.

To learn more, please visit the American Himalayan Foundation Healthcare blog and the Hospital and Rehabilitation Centre for Disabled Children.

Athlete images courtesy of Wikipedia.

Leave a Reply